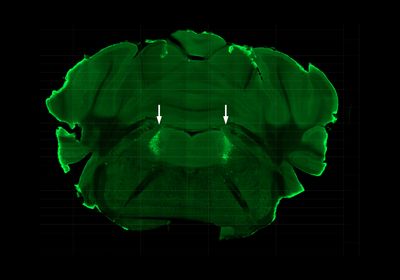

ABOVE: A cross-section of mouse brain highlighting the locus coeruleus (arrows), where the hormone FGF21 acts to sober up drunk mice Mihwa Choi

Fibroblast growth factor 21, usually abbreviated FGF21, is a hormone known to be induced by various metabolic stresses, including fasting and alcohol consumption in both humans and mice. It has also been shown to reduce alcohol intake and stimulate water drinking in animal models, functions that may have evolved to regulate alcohol consumption and prevent its potentially harmful consequences—after all, a small mammal that eats too many fermenting fruits could find itself in trouble very quickly.

See “Controlling Cravings”

Now, scientists have discovered one more property of this hormone: without it, drunk mice take longer to recover their motor skills, whereas a much larger pharmacologic dose speeds up the recovery. The effect, reported yesterday (March 7) in Cell Metabolism, is mediated by the activation of noradrenergic neurons in a region of the brainstem that regulates arousal and alertness.

The findings could lead to clinical interventions for alcohol poisonings, the authors say—though experts caution that a ‘sobering’ drug could be misused.

The team behind the work, led by UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers David Mangelsdorf and Steven Kliewer, exposed control and mice engineered to lack FGF21 to a single dose of ethanol—an amount equivalent to the volume that would get a human drunk enough to pass out, explains Mangelsdorf, who is also affiliated to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Then, the researchers tested the animals’ “ability to wake up,” Mangelsdorf says; that is, they put them on their backs and assessed how often they could right themselves. Mice unable to produce the hormone took nearly two hours longer to recover this righting reflex than the nonengineered controls (5.8 vs 3.9 hours, on average).

The team then tested whether a pharmacologic dose of FGF21 roughly a thousand-fold higher than that which naturally occurs in mice could reduce the time required for recovery in nonengineered mice. Indeed, the mice were able to right themselves about 1.5 hours sooner than mice that didn’t receive the hormone. Notably, however, neither the absence nor additional intake of FGF21 altered the rate at which alcohol was cleared from the animals’ blood, which suggests the hormone does not affect ethanol breakdown.

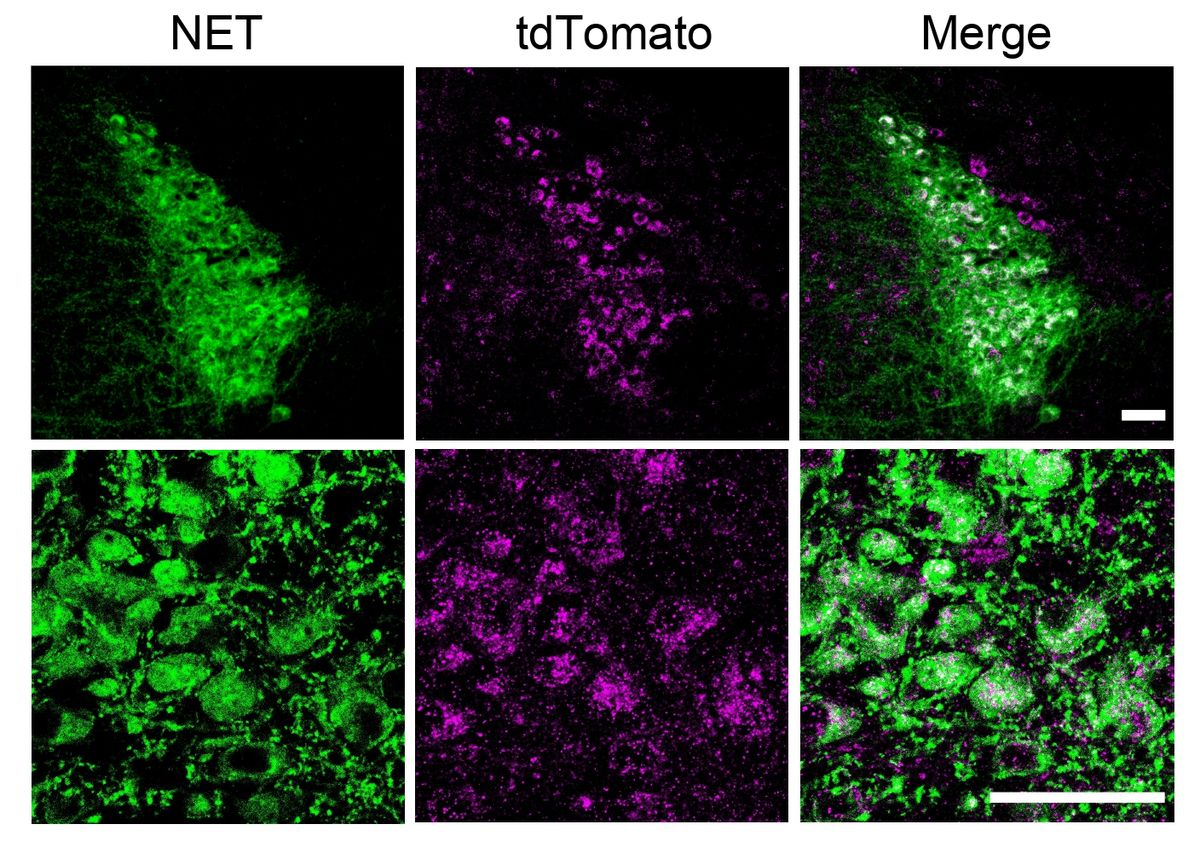

The effect of the hormone was absent in transgenic mice engineered to lack the receptors for FGF21 in noradrenergic neurons located in the locus coeruleus, a region in the brainstem involved in mediating arousal, alertness, and attention. The study’s results point to these neurons as essential for FGF21 to exert its sobering effect.

While it is unknown whether these FGF21’s effects translate to humans, University of Iowa neuroendocrinologist Kyle Flippo says he “would anticipate” they do, based on the current knowledge in the field. “I think, physiologically, it plays an important role, but I don’t know if you would want to give humans pharmacologic FGF21 to prevent the sedative effects of alcohol intoxication,” says Flippo, who did not participate in the study. He adds he is “skeptical of the clinical application that this might have in humans” because it’s important that humans are “able to feel when they’re . . . becoming intoxicated,” for instance, to prevent dangerous behavior.

Mangelsdorf, who along with Kliewer is founder of Atias Pharma, LLC and coauthor of a patent related to this work, says he thinks “that the most useful treatment may be for patients who come into emergency rooms with acute alcohol poisoning, because being able to increase their alertness” would be helpful for preventing them from choking, aspirating their own vomit—which can lead to death—and evaluating them for treatment for other injuries. Pharmacologic FGF21 is currently being tested in various clinical trials to assess some of its other functions.