ABOVE: The vaginal microbiome may play an important role in key aspects of women’s health, including susceptibility to infections and cancers. © iStock, Sewcream

Over the past decade, there has been an explosion of scientific research on the gut microbiome. Scientists have explored the role of this complex microbial community in just about every aspect of human health, including cancer, immune function, and even neurodegenerative disease.

By comparison, the vaginal microbiome has received very little attention, despite the prevalence of bacterial vaginosis (BV), which occurs when the vaginal microbiome shifts into a dysbiotic, or unhealthy, state. BV plagues approximately 30 percent of reproductive-age women in the United States; in some countries, more than 50 percent of women may be affected.1,2

While many people consider the pain, burning, itching, and strong odor characteristic of BV to be merely a nuisance, this condition can have enormous effects on patients’ lives. “People will tell you that BV has destroyed their sense of intimacy with their partner and that it makes them feel ashamed. It has really destroyed their sense of well being,” said Caroline Mitchell, a reproductive biologist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

However, the impacts of vaginal dysbiosis extend even further, with important health consequences not just for women, but for humanity as a whole. That’s because research indicates that the vaginal microbiome could influence the propagation of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including chlamydia, gonorrhea, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).3 BV has also been linked to infertility and risk of preterm birth, which is itself associated with an increased risk of lifelong cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurodevelopmental conditions in the child. 4–7

The two classes of antibiotics recommended for the treatment of BV are the same two classes that were recommended in 1982. That is atrocious.

-Caroline Mitchell, Massachusetts General Hospital

“The vaginal microbiome, one could say, is probably the most important microbiome because none of us would be here without pregnancy and birth,” said Craig Cohen, a reproductive health researcher at the University of California, San Francisco.

Despite the negative consequences of vaginal dysbiosis, much remains unknown about the disorder, and new treatments are virtually nonexistent. “The two classes of antibiotics recommended for the treatment of BV are the same two classes that were recommended in 1982,” said Mitchell. “That is atrocious.” While these antibiotics reduce symptoms in the short term, more than half of women will experience a BV recurrence.8

“One of the reasons this field has not progressed further is that women's health is drastically underfunded,” Mitchell said. “It is really a disservice to women.”

Now, Mitchell and other dedicated scientists are hard at work expanding the understanding of the understudied vaginal microbiome. They are researching the roles of the different microbes within this community, attempting to identify the mechanisms through which they contribute to health or disease and figure out how bring an unhealthy microbiome back into balance.

Who’s who of the vaginal microbiome

A healthy gut microbiome contains a diverse array of microbes that can vary dramatically between individuals.9 The healthy vaginal microbiome, in contrast, is often dominated by one of four Lactobacillus species: L. crispatus, L. iners, L. paragasseri, and L. mulieris.10 Of these types, L. crispatus seems to be associated with optimal health. “Crispatus is the golden child of all the lactobaccilli,” said Melissa Herbst-Kralovetz, a vaginal microbiome researcher at the University of Arizona. A microbiota dominated by L. iners, on the other hand, has been linked to a greater risk for developing BV.11

Crispatus is the golden child of all the lactobaccilli.

-Melissa Herbst-Kralovetz, the University of Arizona

When the lactobaccilli lose dominance, a diverse array of anaerobic bacteria, including Gardnerella vaginalis, Fannyhessea vaginae, and Prevotella bivia, may begin to flourish and cause dysbiosis.12 However, no single microbe seems sufficient to cause BV, and many BV-associated bacteria are also found in healthy women.13

“It’s really this polymicrobial consortium of bacteria,” said Herbst-Kralovetz. “There’s not just one agent, and it doesn't always look the same in every woman.” This makes the condition difficult to study, let alone prevent or treat.

Another difficulty in studying the vaginal microbiome is that there simply aren’t good animal models that allow scientists to test hypotheses. “Humans are the only species with a Lactobacillus-dominant vaginal microbial community,” said Mitchell. “Rats and mice in the very few rat and mouse vaginal microbiome studies have a low-diversity vaginal community, but it's mostly Streptococcus or Enterococcus, which are super different than Lactobacillus. And every nonhuman primate, from chimpanzees to rhesus macaques, has a diverse vaginal community that's much more like BV as their normal state.”

Nooks and crannies

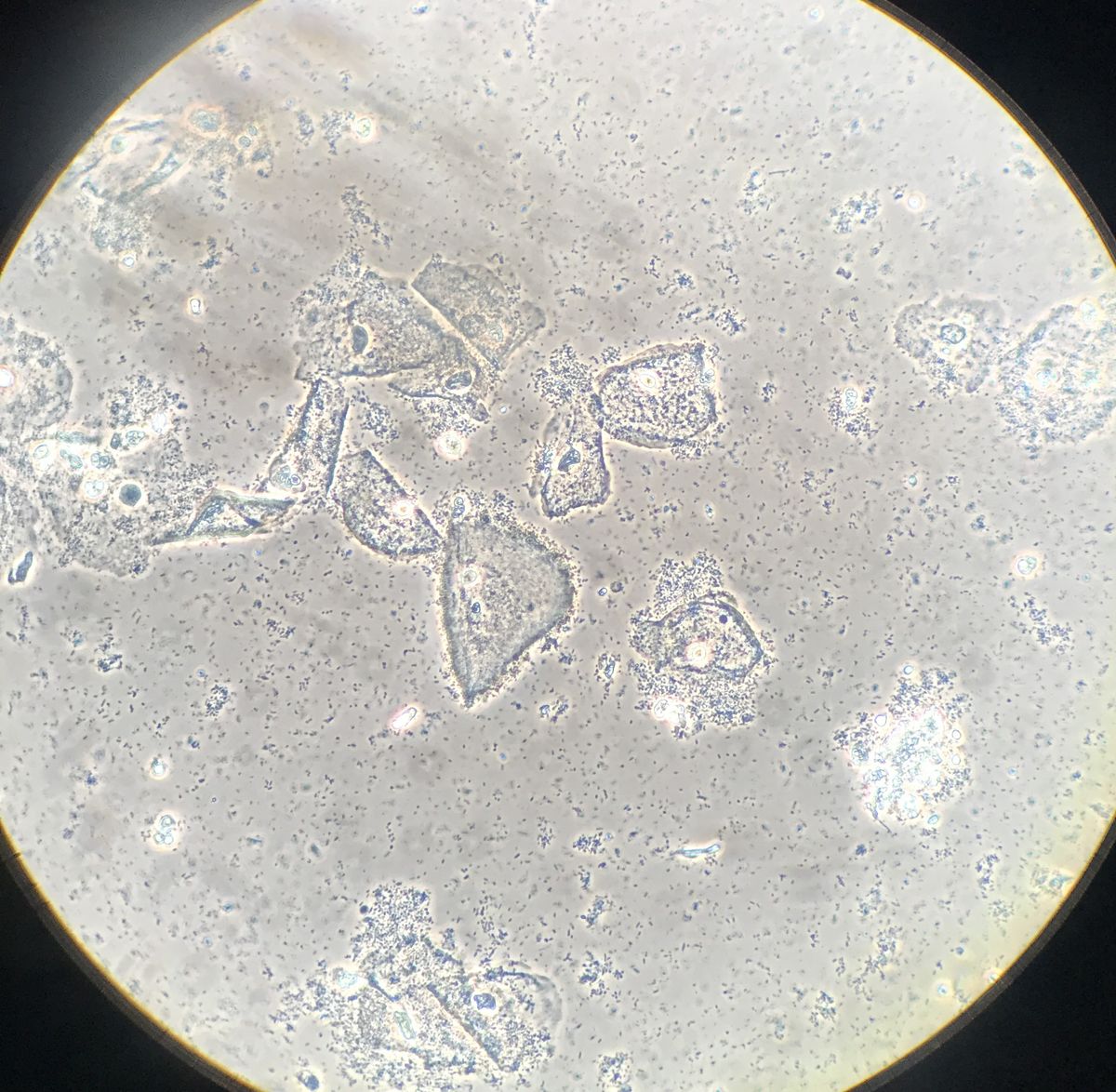

In the absence of good animal models, some scientists, including Herbst-Kralovetz, are building three-dimensional tissue models to study how different bacteria exert beneficial or detrimental effects on cells in the female reproductive system.

Herbst-Kralovetz was originally interested in studying single microbe-driven STIs, but she soon became intrigued by the diverse group of species that cause BV. For a long time, said Herbst-Kralovetz, “We didn't even know what those individual bugs did. So that's what we've been working on for over a decade: better understanding the individual contributions of these BV-associated bacteria.”

Herbst-Kralovetz creates her models using a rotating wall vessel bioreactor. These bioreactors were first designed by NASA to model microgravity here on Earth. However, researchers soon found that the modeled microgravity environment allowed them to grow cells into three-dimensional aggregates, which are more similar to normal human tissues than a single layer of cells in culture.14

This three-dimensional structure is important for modeling the intricate tissues of the vagina. “When you see a diagram of a vagina, it looks like an open tube, but in reality, it has all these folds and invaginations. And that’s where the bacteria like to hang out, in those nooks and crannies,” said Herbst-Kralovetz. “Using these models, we can visualize the host-bacteria interactions using things like scanning electron microscopy.”

Herbst-Kralovetz is particularly interested in understanding the effects of microbes on vaginal and cervical cells in the context of cancer development. Work by Herbst-Kralovetz and many others has indicated that the composition of the vaginal microbiome associates with cervical cancer. Some studies show that women whose microbiomes were dominated by non-lactobacilli species were more likely to be infected with human papillomavirus (HPV) and had a higher risk for cervical cancer.15,16

Are these bacteria driving us towards cancer? Or are they just passengers that like to grow in the cancer environment?

-Melissa Herbst-Kralovetz, the University of Arizona

However, she said, this link presents a chicken-and-egg scenario. “Are these bacteria driving us towards cancer? Or are they just passengers that like to grow in the cancer environment?”

So far, Herbst-Kralovetz has used her models to study the impacts of several individual species of BV-associated bacteria on processes related to cancer development, including inflammation and production of the oncogenic metabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate.12,17

Now, she said, “We've started to create these polymicrobial cocktails, where we can put the bacteria together and then see if they behave the same way that they behaved individually when they're together with their friends.” Some species, for example, might not colonize the vaginal or cervical environment very well on their own, but prove far more dangerous with the help of other biofilm-forming species.18

Herbst-Kralovetz hopes that this research can inform the development of more targeted therapies. Once scientists identify the real “bad guys” of BV, they might be able to develop drugs that target these microbes specifically.

While Herbst-Kralovetz’s three-dimensional vaginal models can provide important mechanistic insights into the relationship between BV-associated bacteria and certain types of STIs and cancers, they can’t help scientists understand HIV acquisition, since they don’t have immune systems. They also can’t get pregnant or give birth, so their usefulness for studying the impact of the microbiome on fertility and preterm birth is also limited. Sometimes, scientists just need to study the real thing.

“I have to do something about this.”

Cohen has been studying how the vaginal microbiome impacts women’s health outcomes for decades, well before the term “microbiome” came into vogue.

During his medical residency in obstetrics and gynecology in the 1990s, he developed a hunch that there might be a link between BV and HIV. Cohen and his colleagues became the first to demonstrate this association: Their study of sex workers in Thailand revealed that individuals with abnormal vaginal flora were more likely to be HIV positive.19

“While I was there, I became completely committed to this work,” said Cohen. “Most of these women were coerced into sex work and at that time, 40 percent of them were living with HIV. And I just thought ‘I have to do something about this.’”

It was not clear whether BV increased the risk of HIV, or vice versa. It was also possible that another factor altogether might increase the risk of contracting both BV and HIV.

In the following years, research accumulated that suggested, if not conclusively proved, a causal role for BV in increasing the risk of contracting HIV.20,21 Cohen found that this risk was more than a women’s health issue: Women with BV were more likely to transmit HIV to their male partners than women who had HIV without BV.22

Cohen hypothesized that optimizing the vaginal microbiome might reduce HIV acquisition and transmission. However, optimizing this microbiome isn’t a straightforward task. Antibiotics can kill some of the BV-associated bacteria, but in the long term, they don’t necessarily restore lactobacillus dominance.

Cohen partnered with the biotechnology company Osel, Inc. to test whether treatment with a specific strain of L. crispatus called Lactin-V after antibiotic treatment could restore a healthy vaginal microbiome and prevent recurrence of BV in women in the United States. In the trial, 45 percent of women who received antibiotic treatment and a placebo had a recurrence of BV compared to only 30 percent of women who received the antibiotic plus Lactin-V.23

In a subset of these women, researchers also measured factors that are thought to contribute to HIV susceptibility, including vaginal inflammation and disruption of the epithelial barrier. They found that Lactin-V treatment associated with lower vaginal levels of interleukin-1α (IL-1α), a proinflammatory cytokine, as well as a reduction in soluble E-cadherin, a protein that indicates epithelial barrier dysfunction.24

In the meantime, Cohen had also come across research by Douglas Kwon, an infectious disease researcher at the Ragon Institute of Massachusetts General Hospital, MIT, and Harvard University. Kwon’s study followed a group of HIV-negative women in South Africa for nearly one year. Over the course of the study, 31 of the 236 women acquired HIV.25 Cohen was struck by the finding that none of the women whose vaginal microbiomes were dominated by L. crispatus contracted HIV during the study.

“Now, we're doing a Lactin-V trial in that cohort to look at whether the application of exogenous Lactobacillus crispatus could produce similar results to [those of] the women who had endogenous Lactobacillus crispatus colonization,” said Cohen.

If we can optimize the vaginal microbiome in a sustainable way, then we could potentially address the sequelae of dysbiosis, including HIV acquisition, preterm birth, and potentially other indications as well.

-Craig Cohen, the University of California, San Francisco

Since vaginal microbiomes can differ substantially between different populations of women, this small trial will confirm whether Lactin-V can effectively colonize these women and reduce inflammation in a manner similar to the trial participants in the United States.26

“If we can optimize the vaginal microbiome in a sustainable way, then we could potentially address the sequelae of dysbiosis, including HIV acquisition, preterm birth, and potentially other indications as well,” said Cohen.

Indeed, a in recent study, researchers administered Lactin-V to pregnant women at high risk of preterm birth. Although there was no control group, only 3.3 percent of the women who received Lactin-V gave birth before 34 weeks of pregnancy compared to 7 percent in a historical group who were judged to be at similar risk.27 While researchers need to investigate further, having a treatment to decrease the rates of preterm birth, “would be groundbreaking,” said Cohen.

Cohen said that the FDA has given Osel the green light to perform two phase 3 definitive trials of Lactin-V, but acquiring funding has been a challenge. Like Mitchell, Cohen is frustrated by how little investment and advancement there has been in treatments for vaginal dysbiosis.

“We hear about large sums of money being invested in other areas like the gut microbiome,” said Cohen. “Here's a condition that affects people with vaginas, the majority of whom would identify as women. And the investment just isn't there.”

Does it take a village?

Lactin-V isn’t the only treatment being tested for restoring balance in the vaginal microbiome. Mitchell and Kwon are testing whether antibiotic treatment followed by a vaginal microbiota transplant (VMT) from a healthy donor can provide long-lasting restoration of Lactobacillus dominance and therefore relief from BV.

“After fecal microbiota transplantation, it sort of seems logical that if transferring a whole microbiome works in one condition, it might work in another,” said Mitchell.

“The idea that the whole vaginal microbial community may be effective has unfortunate precedent,” Mitchell added. Although this trial is one of the first times that VMT will be used to treat BV, there is a previous instance of VMT being used to cause BV, in a set of experiments that Mitchell called highly unethical. In the 1950s, the gynecologist Herman Gardner and the microbiologist Charles Dukes at Baylor University attempted to prove that a single type of bacteria caused BV by administering it to 13 healthy women.28 They also administered “material from the vagina” of women with BV to another group of 15 women. The women who were experimented on are described only as “volunteer clinic patients” and there is no mention of informed consent procedures.

Only one woman who was administered the single type of bacteria developed symptoms, but 11 of the 15 who received the full consortium of vaginal microbes did. Today, the BV-associated bacteria that Gardner tested carries his name; it’s known as Gardnerella vaginalis.

If a consortium of microbes is important for causing BV, a consortium might also be important for its cure. While L. crispatus-dominated communities seem to be most strongly associated with optimal vaginal health, some researchers hypothesize that other less abundant types of bacteria or phages might play important roles in supporting the lactobacilli.29 Furthermore, there are many different strains of L. crispatus, which vary substantially in functional capabilities and interactions with pathogenic bacteria.30

“One hypothesis about why Lactin-V is not universally successful is that it's only one strain,” said Mitchell. “Maybe you need multiple strains; maybe microbial friends are helpful. A whole community might be better because we just don't know what the supporting cast is.”

One very preliminary trial from researchers at Hadassah-Hebrew University and the Weizmann Institute of Science indicated that a microbiome transplant may be an effective approach for some women. In the trial, two of the five women with recurrent BV achieved long-lasting remission after just one VMT treatment and two others achieved the same after three treatments.31

However, larger placebo-controlled trials are needed to determine efficacy. Mitchell and Kwon’s trial will include 134 women, half of whom will receive a placebo.

Even if VMT turns out to be extremely effective, it still has a fatal flaw. “The downside is that it’s definitely not scalable,” said Mitchell. To ensure safety, each donor must undergo an extensive — and expensive — battery of tests, including analyzing vaginal pH, liver function, and complete blood counts and screening for semen contamination and several infectious diseases.

Whether VMT works or not, we're going to learn so much about the biology that I'm really excited about.”

-Caroline Mitchell, Massachusetts General Hospital

If VMT is effective, Mitchell said, “the next steps would be to use the information we gained from this study to design a synthetic intervention.” Starting with the entire consortium, they hope to work backwards to find the “secret sauce,” the right combination of microbes that are needed to restore a healthy vaginal community.

“Whether VMT works or not, we're going to learn so much about the biology that I'm really excited about,” said Mitchell.

Through the efforts of Mitchell and other vaginal microbiome researchers, scientists may one day build a picture of the full spectrum of microbes in the vagina that influence health and disease. In optimizing these communities, they aim to improve quality of life for women, their partners, and their children.

References

- Koumans EH et al. The Prevalence of Bacterial Vaginosis in the United States, 2001–2004; Associations With Symptoms, Sexual Behaviors, and Reproductive Health. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2007;34(11):864.

- Bautista CT et al. Bacterial vaginosis: a synthesis of the literature on etiology, prevalence, risk factors, and relationship with chlamydia and gonorrhea infections. Military Medical Research. 2016;3(1):4.

- Adapen C et al. Role of the human vaginal microbiota in the regulation of inflammation and sexually transmitted infection acquisition: Contribution of the non-human primate model to a better understanding? Frontiers in Reproductive Health. 2022;4.

- Vitale SG et al. The Role of Genital Tract Microbiome in Fertility: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;23(1):180.

- Fettweis JM et al. The vaginal microbiome and preterm birth. Nat Med. 2019;25(6):1012-1021.

- Crump C. An overview of adult health outcomes after preterm birth. Early Hum Dev. 2020;150:105187.

- Ravel J et al. Bacterial vaginosis and its association with infertility, endometritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021;224(3):251-257.

- Bradshaw CS et al. High Recurrence Rates of Bacterial Vaginosis over the Course of 12 Months after Oral Metronidazole Therapy and Factors Associated with Recurrence. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;193(11):1478-1486.

- Shreiner AB et al. The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015;31(1):69-75.

- Jimenez NR et al. Commensal Lactobacilli Metabolically Contribute to Cervical Epithelial Homeostasis in a Species-Specific Manner. mSphere. 2023;8(1):e00452-22.

- Carter KA et al. Epidemiologic Evidence on the Role of Lactobacillus iners in Sexually Transmitted Infections and Bacterial Vaginosis: A Series of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2023;50(4):224.

- Łaniewski P, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Bacterial vaginosis and health-associated bacteria modulate the immunometabolic landscape in 3D model of human cervix. npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 2021;7(1):1-17.

- Margolis E, Fredricks DN. Chapter 83 - Bacterial Vaginosis-Associated Bacteria. In: Tang YW et al., eds. Molecular Medical Microbiology (Second Edition). Academic Press; 2015:1487-1496.

- Barrila J et al. Organotypic 3D cell culture models: using the rotating wall vessel to study host–pathogen interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(11):791-801.

- Norenhag J et al. The vaginal microbiota, human papillomavirus and cervical dysplasia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2020;127(2):171-180.

- Wang H et al. Associations of Cervicovaginal Lactobacilli With High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Infection, Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2019;220(8):1243-1254.

- Maarsingh JD et al. Immunometabolic and potential tumor-promoting changes in 3D cervical cell models infected with bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria. Commun Biol. 2022;5(1):1-13.

- Muzny CA et al. Host-vaginal microbiota interactions in the pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2020;33(1):59-65.

- Cohen CR et al. Bacterial vaginosis and HIV seroprevalence among female commercial sex workers in Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS. 1995;9(9):1093-1097.

- Myer L et al. Bacterial vaginosis and susceptibility to HIV infection in South African women: a nested case-control study. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(8):1372-1380.

- van de Wijgert JHHM et al. Bacterial Vaginosis and Vaginal Yeast, But Not Vaginal Cleansing, Increase HIV-1 Acquisition in African Women. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;48(2):203.

- Cohen CR et al. Bacterial vaginosis associated with increased risk of female-to-male HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort analysis among African couples. PLoS Med. 2012;9(6):e1001251.

- Cohen CR et al. Randomized Trial of Lactin-V to Prevent Recurrence of Bacterial Vaginosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(20):1906-1915.

- Armstrong E et al. Sustained effect of LACTIN-V (Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05) on genital immunology following standard bacterial vaginosis treatment: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Microbe. 2022;3(6):e435-e442.

- Gosmann C et al. Lactobacillus-Deficient Cervicovaginal Bacterial Communities Are Associated with Increased HIV Acquisition in Young South African Women. Immunity. 2017;46(1):29-37.

- Ravel J et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108(supplement_1):4680-4687.

- Bayar E et al. Safety, tolerability, and acceptability of Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05 (LACTIN-V) in pregnant women at high-risk of preterm birth. Benef Microbes. 2023;14(1):45-55.

- Gardner HL, Dukes CD. Haemophilus vaginalis vaginitis: a newly defined specific infection previously classified non-specific vaginitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1955;69(5):962-976.

- Yockey LJ et al. Screening and characterization of vaginal fluid donations for vaginal microbiota transplantation. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):17948.

- Argentini C et al. Evaluation of Modulatory Activities of Lactobacillus crispatus Strains in the Context of the Vaginal Microbiota. Microbiol Spectr. 10(2):e02733-21.

- Lev-Sagie A et al. Vaginal microbiome transplantation in women with intractable bacterial vaginosis. Nat Med. 2019;25(10):1500-1504.

This story was originally published on Drug Discovery News, the leading news magazine for scientists in pharma and biotech.