In order to make their models, such as this sea anemone (Phymactis florida), as lifelike as possible, the Blaschkas consulted leading experts, referenced scientific illustrations, and in some cases, even purchased living creatures to serve as references for sculptures.

While on commission for Harvard University, Rudolf Blaschka also traveled to get firsthand looks at new plants to sculpt. Following an 1892 journey to Jamaica, for example, he was able to re-create this flowering Pride of Barbados, or peacock flower (Caesalpinia pulcherrima).

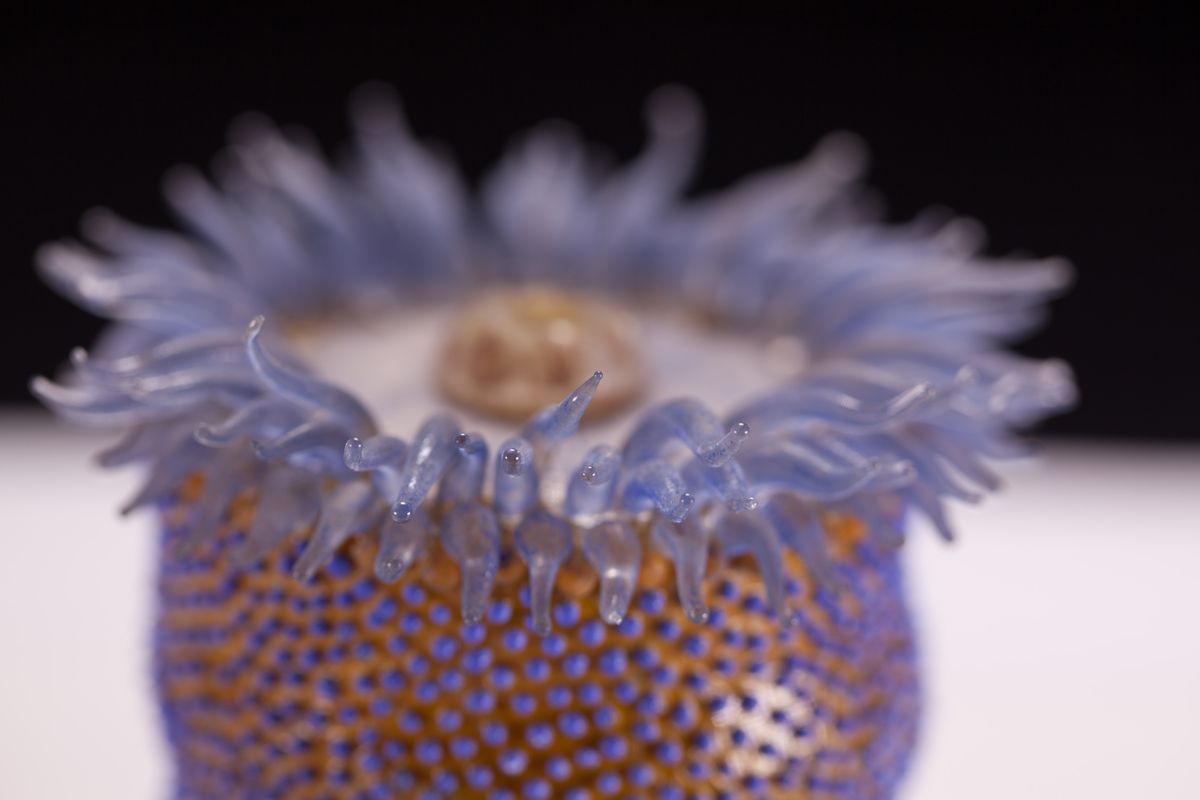

Because of the pair’s commitment to accuracy, the Blaschka models were considered far better representations of the animals they depicted, in this case the sea slugs Ercolania siottii (left) and E. uziellii (right), than other models of the era, which were made of wax or papier-mâché.

This golden bellapple (Passiflora laurifolia) from 1893 highlights the father-and-son duo’s careful attention to textures. In some cases, the natural look of leaves was recreated by assembling multiple layers of glass with different metal contents.

In some cases, the Blaschkas sculpted the same organisms across multiple stages of life. That may explain the inclusion of the flowering offshoot snaking away from the signature rosette arrangement of this succulent (Echeveria secunda) model from 1889.

In addition to healthy organisms, Rudolf Blaschka crafted models of plants infected by common pathogens to serve as educational tools. One example is this apple (Malus pumila) from 1932 marked by the telltale blemishes of an apple scab infection caused by the fungus Venturia inaequalis.

Read the full story.