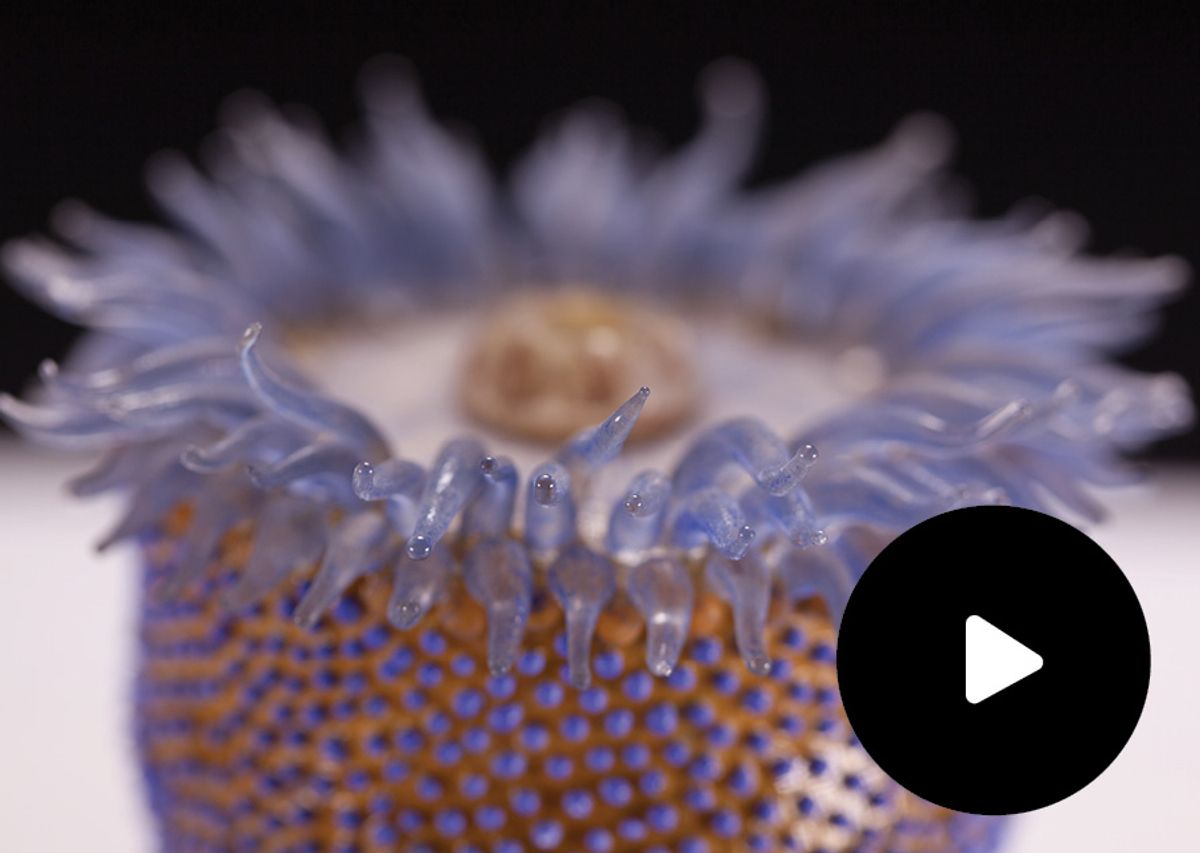

ABOVE: THE WARE COLLECTION OF BLASCHKA GLASS MODELS OF PLANTS, HARVARD UNIVERSITY HERBARIA / HARVARD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY © PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD COLLEGE

In the late 19th century, the rise of natural history museums and their increasing popularity as a means to acquaint the public with the scientific world introduced a pressing new problem. Preserving once-living things was a challenge, and the resulting specimens were poor representations of the vivid, beautiful flora and fauna they had been in life. Flowers pressed flat grew dull, and invertebrates floating in alcohol faded and lost their defining features, becoming muted and blobby.

As an alternative, many museums and universities commissioned or purchased collections of Blaschka models: exquisitely crafted, scientifically accurate glass sculptures of plants and sea creatures used for both display and scientific study that were made by father-and-son duo Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, who hailed from a long line of glassworkers.

Before Rudolf was born, Leopold, then a jewelry maker who excelled at glass sculpting, had embarked on an 1853 sea voyage from his home in what was then Czechoslovakia to the US. It was during this trip that he first spotted a bioluminescent jellyfish beneath the surface of the water and was inspired to re-create sea life with glass, writes Catherine “Drew” Harvell, professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at Cornell University, in her book on the Blaschkas, A Sea of Glass.

Over the ensuing decades, Rudolf trained under and partnered with his father, and the duo became known for their meticulous attention to detail and ability to re-create lifelike replicas that wowed researchers and enthusiasts. “It grew into this obsession . . . to the point where [Leopold] contacted the leading scientific experts of the day to ask these details of what these things looked like and how they lived,” Harvell tells The Scientist. The pair also purchased live invertebrates, keeping them in aquariums in their home as they worked to emulate the animals in glass. “They really, really cared about the scientific credibility of their work.”

Between 1863 and 1890, the Blaschkas created roughly 10,000 models of some 800 different marine invertebrate species, Harvell says—work that Rudolf continued meticulously after Leopold’s death in 1895. Late in Leopold’s life, they were approached by George Goodale, the founding director of Harvard’s Botanical Museum, who was so floored by the models that he commissioned an entire “garden” of flowers and plants that numbered in the thousands. Rudolf, who never had children of his own, completed the collection in 1936, just three years before his death. Among the collection were examples of plants infected by common pathogens, including a rotting apple and a blight-infected pear, used to study botany and agricultural pests.

The marine models are now scattered around the world, with large collections at the Harvard Museum of Natural History and Cornell University. Harvell mentions that Cornell professors still use the models as educational materials, adding that the vivid creations are invaluable for inspiring interest in marine biology in students.

They also serve a second, contemporary purpose: Frozen in time, the glass sculptures offer a glimpse of species, such as some deep-water octopuses, that are now endangered or extinct. “It’s a sad irony that the ambassadors in glass have survived 170 years where some of the animals themselves have not,” Harvell says.