ABOVE: A vet and technician take a sample from a dog for use in PetDx’s OncoK9 test, which screens cell-free DNA for genomic alterations associated with cancer. PETDX

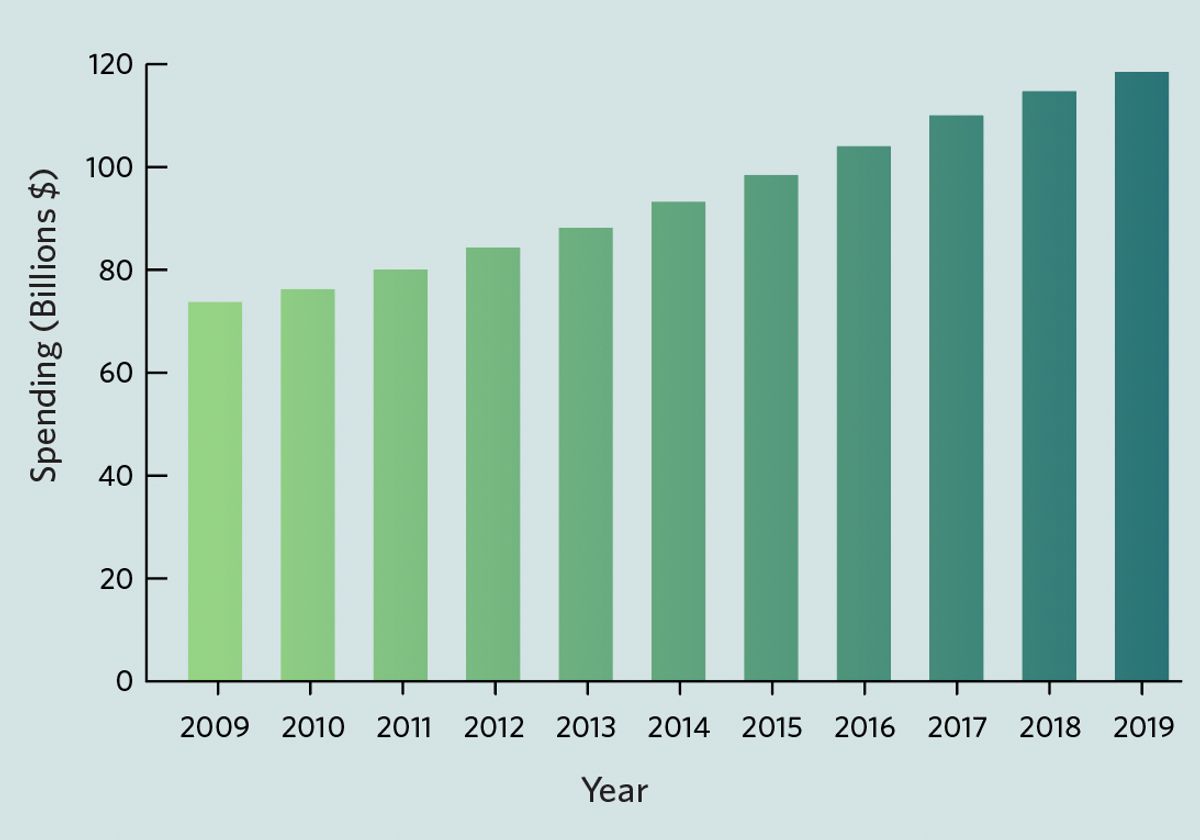

As people around the world hunkered down in their homes during the COVID-19 pandemic, many decided to add a four-legged companion to their families. Although surveys have struggled to quantify these changes in pet ownership, some have estimated that approximately 23 million US households adopted an animal between March 2020 and May 2021. The seemingly heightened interest in cats and dogs has led some industry analysts to predict a boost in pet-related spending. Morgan Stanley, for example, forecasts that the total amount that US pet owners spend on their animal companions will grow from approximately $118 billion in 2019 to $275 billion by 2030.

A big chunk of this growth is likely to come from veterinary care—the second-largest area of consumer spending, after foods, in the pet industry—and from the emerging sector of diagnostics in particular. Products already on the market include urine tests for kidney disease, tissue biopsies for cancer, and blood tests for infectious diseases. As pets become integrated into families—as evidenced by many pet owners viewing themselves as pet “parents” rather than “owners”—people are increasingly willing to open their wallets for the nonhuman members of their homes.

“We’re generally seeing that pet owners are just much more open to specialty care and to advanced diagnostics,” says veterinary oncologist Andi Flory, chief medical officer and cofounder of the California-based diagnostics company PetDx. “And they’re treating their pets very much like family and have come to expect the same level of healthcare for their pets they do for themselves.”

This demand has also given rise to a booming pet genomics industry, enabled by technological advances that have lowered the cost and increased the efficiency of DNA sequencing. Genomic-based tools can now be found in direct-to-consumer DNA tests that pet owners can use at home, and as part of the diagnostics and treatment processes in veterinary clinics. Most are only available for dogs—the most popular pet in the US—and many in the industry are interested in targeting one class of disease in particular: cancer, one of the leading causes of canine mortality.

Yet while genomics-based tools promise an exciting new frontier for pet diagnostics, pet owners should approach them with caution, some experts note. Unlike treatments and diagnostics for humans, which are overseen by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), medical products for pets are not required to undergo regulatory review. On top of that, much of the science behind many of these products is still in its early stages—and more research is needed to determine their true utility. “I think it’s fantastic that these technologies are being developed—they’re going to be really powerful one day,” says Elinor Karlsson, director of the vertebrate genomics group at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University. However, she adds, there are important open questions that need to be addressed.

Screening dogs

According to the American Veterinary Society, approximately one in four dogs will be diagnosed with cancer at some time in its life. Considering just dogs over the age of 10 years old, that number jumps to an estimated 50 percent. Veterinarians typically don’t have many diagnostic tools other than invasive tissue biopsies and lower-precision techniques such as X-ray and ultrasound at their disposal. Methods such as computed tomography (CT) that can provide more-detailed images are often expensive and prioritized for human use, according to Cheryl London, a veterinary oncologist at Tufts University.

To address this problem, some companies are working on applying new genomic tools to enable better cancer screening techniques for dogs. Last year, PetDx launched OncoK9, a liquid biopsy test based on a simple blood draw. According to information available on the PetDx website, OncoK9 works by examining DNA floating outside cells, also known as cell-free DNA, for genomic alterations associated with cancer. The approach relies on the fact that cancerous cells die and break off from the primary tumor, ending up in the bloodstream, where they release their mutation-containing DNA. The test is available in veterinary clinics across North America for around $500 a pop. The company recommends all dogs be screened annually with OncoK9 from age seven (and younger for breeds at risk for cancer at an earlier age).

To validate its tool—a rare practice in a largely unregulated market, notes Daniel Grosu, PetDx’s president and CEO—the company recently examined blood samples collected from approximately 1,100 dogs across 41 clinical sites in six countries. Fewer than half of the dogs had a cancer diagnosis, with the rest presumed to be cancer-free at the time of enrollment. Researchers used OncoK9 to screen for more than 40 cancer types, including those common in dogs, such as lymphoma (cancers that begin in immune cells known as lymphocytes), hemangiosarcoma (which affects blood vessel–lining cells), and osteosarcoma (bone cancer).

In a paper published in PLOS ONE this April, the company reported that the test’s overall specificity (a measure of its ability to avoid false positives) was 98.5 percent and its overall sensitivity (reflecting its ability to identify true positives) was 54.7 percent, although the sensitivity for different types of cancers varied. For example, OncoK9 identified 106 of 113 cases of lymphoma, but only 4 of 18 cases of anal sac cancers. In general, the test performed much better for larger and more highly metastasized cancers.

“We are very proud of the very low false positive rate of our test,” Grosu tells The Scientist. The cancers with lower detection rates are “an opportunity for growth and improvement” for the company, he adds. “This is really a version-one product. We are just getting started—we barely launched a year ago, and we have a lot of ongoing R&D to improve both the sensitivity and the specificity of the test.”

Flory notes that PetDx is working to educate veterinarians about how to interpret and utilize the results of these OncoK9 tests. A positive result “should never be used as a sole basis for making important decisions for the patient like treatment or euthanasia,” she says. “And a negative result should always be followed, especially if that patient is suspected to have cancer, because false negatives and false positives can occur.”

While PetDx leads the market in genomic cancer diagnostics, there are other companies that offer early screening using different techniques. The Nevada-based company Volition Veterinary, for example, offers a blood test for cancer based on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), a method that uses antibodies to detect the presence of specific molecules. Volition’s test, dubbed Nu.Q, is designed to identify nucleosomes, clumps of DNA wrapped around proteins, that are released from tumors into the bloodstream. The company claims to be able to detect a handful of cancers, such as lymphoma and hemangiosarcoma, some at their early stages—and recommends its test be used as part of the annual wellness check for dogs that are seven years or older.

Too early?

Some experts note that there are limitations to using such tools in diagnostics, particularly in cancer’s early stages. One issue is that the volume of tumor DNA in the blood can be small during this phase, unlike in advanced metastatic cancer, when there is a ton of tumor DNA floating around, says Karlsson, who is currently examining whether liquid biopsies developed for humans are effective in dogs. “What we don’t really understand yet is exactly how to use that information,” she explains. “How much tumor DNA is actually a problem?”

To address this question, researchers need to better characterize the genetic variation in dog populations, according to Karlsson. Doing so will help scientists determine how often the mutations seen in tumor DNA occur as a normal part of aging, and so better identify when there is actually a cancer that’s going to grow and be a medical problem. Without this information, using techniques like liquid biopsies for early cancer diagnostics can lead to tricky veterinary ethics questions, Karlsson says. For example, if an older dog with a pre-existing condition like diabetes gets diagnosed with a slow-growing cancer that would not significantly affect his health during his lifetime, would that be worth diagnosing? “Right now, we don’t diagnose those cancers,” she adds.

Cancer screening tools also come with certain risks, says Lisa Moses, a veterinarian and bioethicist at Harvard Medical School. Pet owners could end up spending a lot of money to get additional testing for their dog—costs that, in the United States at least, are almost always paid out-of-pocket—only to find that there are few therapeutic options once a diagnosis is made. There are emotional costs to consider, too. “It can be really, really distressing and can impact things in a downstream way that may not be obvious when you first think about it,” Moses says. “Things change in the way you feel about the decisions you make and how you plan for your life when you get this kind of news.”

Flory responds that while there may not be drugs available for every type of cancer, there are other treatment options, such as surgery to remove the tumor or palliative care when other treatment isn’t possible, that might be indicated as a result of a diagnostic test. “If cases can be recognized before patients are ill, we know that has a prognostic benefit—that patients do better when they start a cancer treatment from a place where they’re feeling well versus when they’re sick,” she says. “It also means that we have a lot more options to give families. . . . There’s always something that we can do.”

As for additional costs, PetDx currently has a scheme in place where pet owners who purchase this test will get up to $1,000 of follow-up evaluations covered, according to Grosu. Based on the data collected to date, “What we found is that in the majority of cases, the cancer is found with between $500 to $800 of additional workup once the veterinarian is on alert that there are cancer-associated genomic alterations in the blood.”

Personalized treatments

It’s not just cancer diagnostics where genomics tools are coming into play. Other companies are using these tools after a diagnosis is made to guide a pet’s treatment. One Health Company, another California-based firm, is using next-generation sequencing to identify mutations that could help select personalized therapies for cancer in canines. (Karlsson and London are both on One Health Company’s scientific advisory board.) The company launched a pilot study of their product, dubbed FidoCure, in 2018. Christina Lopes, the firm’s CEO and cofounder, says that her company has helped expand the number of targeted treatment options, such as poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors—drugs that block DNA-repairing enzymes—for dogs carrying mutations in BRCA genes, from 1 to 12. To date, they’ve assessed approximately 3,000 cancer cases, and according to the company’s website, they plan to grow that number to 10,000 by the end of 2023.

To deal with the lack of regulation of pet therapeutics and diagnostics, FidoCure only employs medical products already approved by the FDA for human use, Lopes says. “We want the best—the most de-risked and validated,” she says. “Then we work with our translational medicine team to translate it back to the dog.”

One Health Company has been working with academic research centers to compare cancers and treatment outcomes in humans and dogs. In one study that was conducted along with Stanford University scientists and presented at this year’s meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, researchers analyzed data from 1,303 dogs with confirmed cases of cancer. The team reported that the tumors in these animals shared similar biological characteristics and responses to treatment with human cancers that had the same mutations. Among dogs given targeted cancer treatments, survival rates were higher when the company’s genomic analyses were used to inform the selection of a particular therapy. According to Lopes, this indicates that targeted therapies picked out through FidoCure can benefit their canine recipients.

Much of the science behind many of these products is still in its early stages—and more research is needed to determine their true utility.

Other pet health companies are also applying genomic tools to aid the treatment of dogs with cancer. Arizona-based Vidium Animal Health, for example, uses next-generation sequencing to characterize canine tumors and uses that information to aid in more specific diagnosis and to recommend personalized treatments.

There are limitations to all genomic tests for cancer, according to London. “While we can detect mutations in dog cancers, we don’t always understand the functional significance and how to target affected pathways,” she says. But companies that provide post-diagnosis tests can draw on the vast knowledge from human medicine, “so there is at least an existing set of data to use for making therapeutic recommendations.”

Lopes says that while the One Health Company isn’t currently offering early cancer screening for dogs, pre-malignancy screening and treatment is something that the company is currently investigating. For now, she adds, they’re continuing to grow their canine cancer datasets and keeping a close eye on companies like GRAIL, whose liquid biopsy tests for early cancer in humans are currently undergoing assessment. “We feel the urgency to help dogs,” Lopes tells The Scientist. “But we look at things as a long game.”

PetDx, too, has plans to expand its toolkit. In the near future, the company aims to release additional applications for OncoK9 in post-diagnostic settings, such as monitoring responses to treatment and long-term cancer recurrences. It also plans to expand into other animals, such as cats. The future of the technology is “what we’re most excited about,” Grosu says. “This is just chapter one of an era of genomic medicine in veterinary medicine.”