ABOVE: The Scientist Staff

In a 1959 lecture, the British physicist and novelist C. P. Snow admonished his Cambridge colleagues that “the intellectual life of the whole of western society is increasingly being split into two polar groups.” Snow was referring to the divide between scholars of science and the humanities, complaining that “literary intellectuals” and “physical scientists” didn’t understand or respect each other. Fast-forward 62 years and the situation has only gotten worse, aggravated by further entrenchment, a decrease in the number of students majoring in the humanities, and a series of global challenges that call for a creative confluence of different types of knowledge.

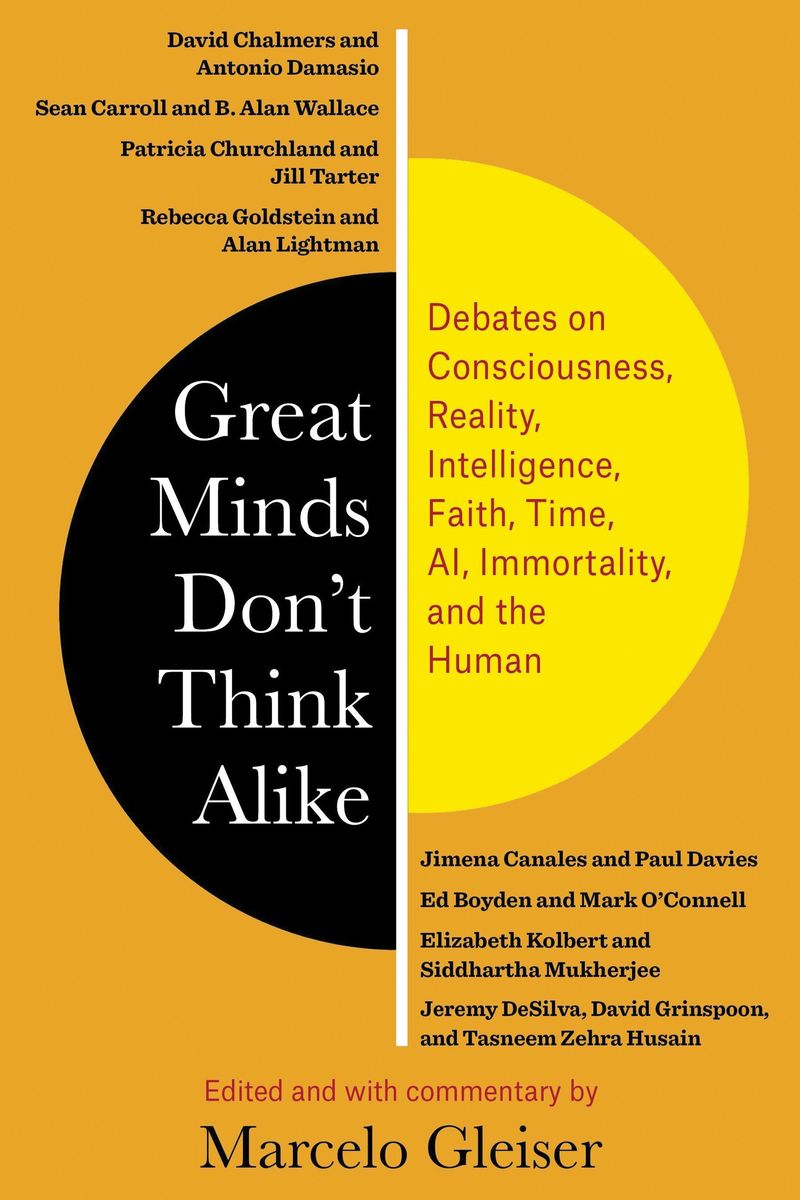

In my new book, Great Minds Don’t Think Alike, I document conversations I had with leading thinkers who bridge the gap between the sciences and the humanities.

The meteoric growth of many fields of scientific knowledge in the past three centuries has led to a model of niche-knowledge. In the sciences, we are trained to be technically adept in a specific subfield; those who dare to cross fields before tenure are usually punished (read: refused tenure). The same hyper-specialization model has percolated through the humanities. Just as typical laser physicists don’t understand astrophysicists, scholars of Classics don’t research Edmund Husserl or Jorge Luis Borges. There are, of course, exceptions, but in both arenas, they are rare. While this focus is required for success in academia, it clashes with the intellectual openness necessary to learn from other fields of inquiry.

This entrenchment of knowledge influences our worldview and the way we teach. Snow’s lament was meant as a wake-up call, an invitation, as yet unheeded, to promote intellectual openness and curiosity. To want to learn from another person, even one with interests far removed from your field of research or with different political or cultural viewpoints, is essential if we are to face the daunting challenges that threaten civilization. And for this to happen, the sciences and the humanities must be open to each other.

Thankfully, the barriers that separate science and the humanities are crumbling. Essential questions, once mostly the province of the humanities, are now part of scientific research. Conversely, science and its uses cannot be separated from moral choices. There is light and there is shadow in every new technology. The nature of free will, the nature of reality, the nature of consciousness, the future of humanity in an increasingly technological world, our future in space, our cosmic loneliness, the limits of scientific knowledge—such issues and many others cross disciplinary boundaries. To look at any of them from a one-sided perspective—either scientific or humanistic—is like looking through a window with the blinds down. With such questions at the forefront, we have the unprecedented opportunity to bring the sciences and the humanities into constructive engagement, and to reposition them as complementary and interdependent facets of human knowledge.

Read an excerpt of Great Minds Don't Think Alike

For example, with CRISPR and other genetic engineering technologies, we are now at the threshold of being able to modify the human genome in ways that benefit or vex future generations. Jennifer Doudna, who shared the 2020 Chemistry Nobel Prize with Emmanuelle Charpentier for the discovery of CRISPR, has stated that she’s grown increasingly uneasy with the potential ethical repercussions of genome editing, citing questions of access, eugenics, privilege, and the difficulty in global regulation. Add to this the fast-growing capabilities of machine-learning and other technologies, and we see how pushing forward a scientific agenda based mostly on commercial interests and absent any humanistic consideration can turn promising technologies into existential risks. Unadvised utopian scenarios of science as a cure for all evils can quickly turn dystopian.

But this is the world we live in, the world that future generations will inherit. Great Minds Don’t Think Alike is a collection of conversations in which I had the privilege of unpacking some of these thorny, modern issues with leading scientists and humanists from various fields. They were part of a larger experiment, the Institute for Cross-Disciplinary Engagement at Dartmouth, created to bring down the cross-disciplinary barriers between practitioners of science and the humanities, through conversations, fellowships, and workshops. To my surprise, we witnessed great support from our guests and diverse audiences for this recalibration. Let us give voice to a need for new avenues of communication and bring down the walls that stop us from learning openly from one another.