ABOVE: © MESA SCHUMACHER

All multicellular animals interact with the microbial life around and inside them. But some have taken the relationship to an extreme, developing specialized organs that house bacterial symbionts and mediate contact between the two parties. A selection of these so-called symbiotic organs is shown below.

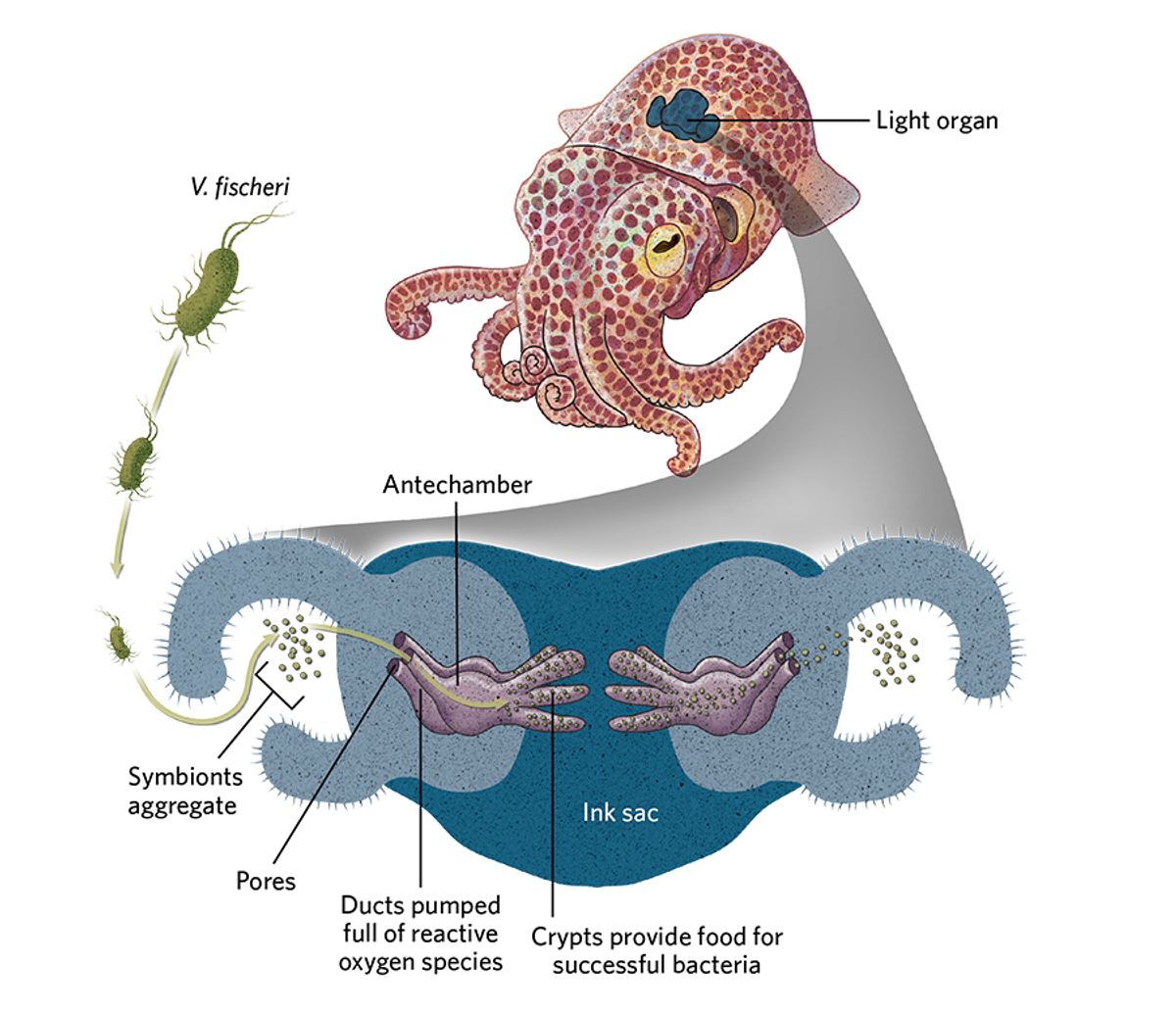

Let There Be Light

Host: Hawaiian bobtail squid (Euprymna scolopes)

Symbiont: Vibrio fischeri

The Hawaiian bobtail squid gets Vibrio fischeri into its light organ by means of chemical signals and a complicated obstacle course that blocks out other bacteria. Once established in the squid’s organ, bacterial symbionts are fed by their cephalopod host, while the microbes luminesce—a trait the squid uses to disguise its silhouette from predators beneath it in the water.

Deep-Sea Symbiosis

Host: Giant tubeworm (Riftia pachyptila)

Symbiont: Candidatus Endoriftia persephone

Giant tubeworms house sulfur-oxidizing bacteria in a specialized organ called the trophosome. The worms funnel sulfides from the mineral-rich water at deep-sea hydrothermal vents to their symbionts, which metabolize those compounds. In exchange, the worms feed on a portion of the bacteria.

Bacterial Sentinels

Host: Beewolf (genus Philanthus)

Symbiont: Genus Streptomyces

Beewolves keep their microbial symbionts in specialized antennal gland reservoirs. These multi-segment structures supply food to the bacteria, which in return produce antimicrobial compounds that protect a beewolf’s offspring from environmental pathogens.

Farming Aids

Host: Attine ants (genera Atta and Acromyrmex)

Symbiont: Genus Pseudonocardia

Fungus-growing ants use microbial symbionts to produce antibiotics to protect their fungus gardens from environmental pathogens. Microbes are stored and fed in crypts all over the ants’ bodies, and are easily transferred through contact between worker ants.

Read the full story.