Multiple studies have reported associations between child health and parental or grandparental lifestyle, while a number of animal and human studies hint at connections between environmental exposures and epigenetic changes in eggs or sperm. However, evidence to support causality in these correlations is lacking in humans. Below are some of the factors frequently studied by researchers interested in the idea of epigenetic inheritance.

Environmental exposures

A multitude of environmental factors have been proposed to influence a person’s health and potentially that of their children. These include exposure to harmful chemicals from cigarettes or pollution, lifestyle circumstances such as exercise and diet, and other factors including age and experience of stress or trauma.

Epigenetic mechanisms?

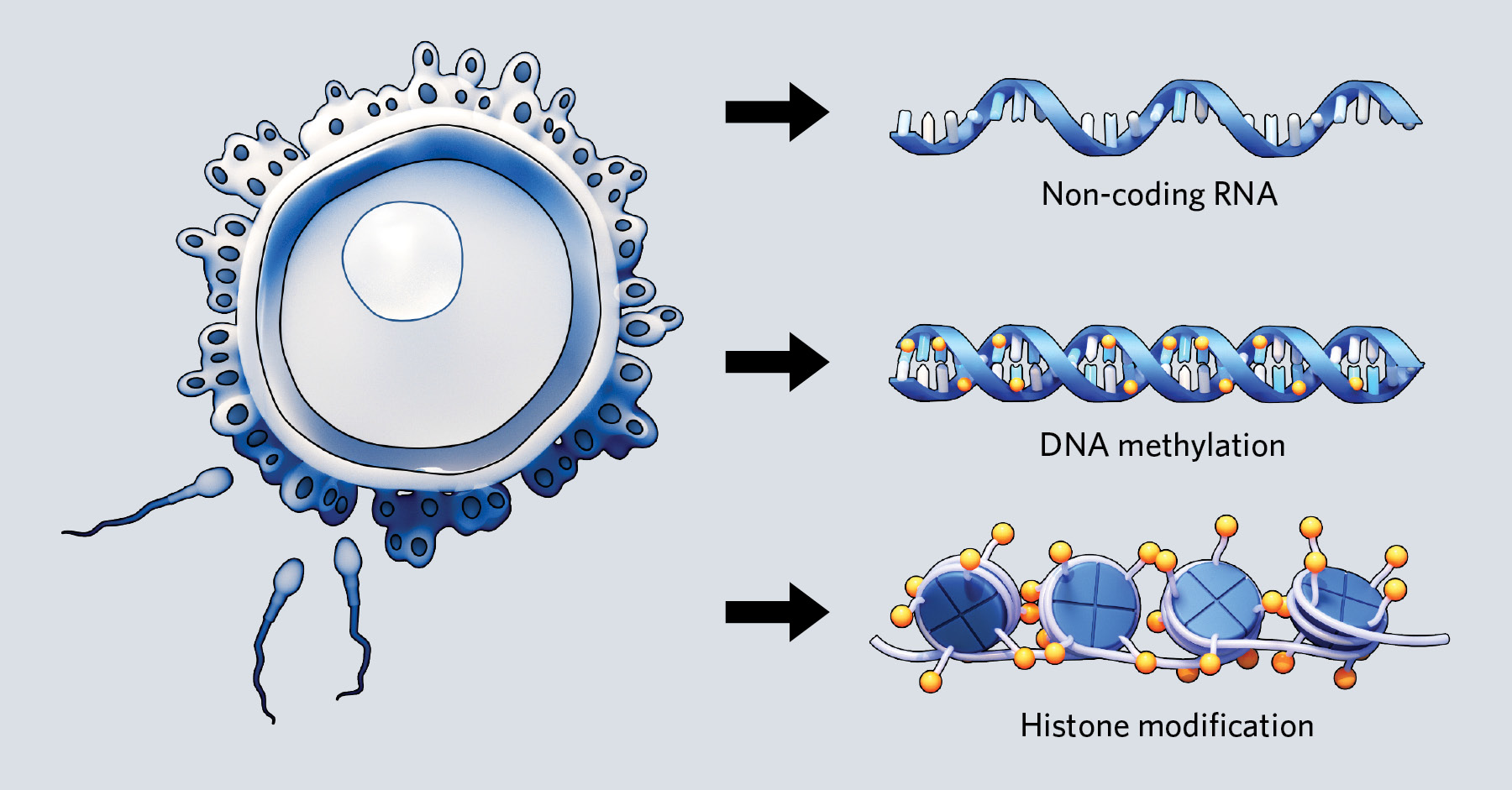

Reported epigenetic changes in gametes, especially sperm cells, in response to environmental factors include changes in the level of certain RNAs, in DNA methylation patterns, and in modifications to histones. The effects of these changes on gene expression and their persistence after fertilization are largely unknown.

Health outcomes

Epidemiological studies have turned up numerous aspects of child health that correlate with parental or grandparental lifestyle. Studied measures of health in kids include birthweight, all-cause mortality, and risk of developing asthma and metabolic diseases, among other conditions.

Confounding factors

There are myriad ways that a parent’s exposure and experiences could influence their child, and most have nothing to do with the epigenome of egg and sperm. Often, a child will experience many of the same environmental conditions as the parent, for example, while particular experiences might influence the way parents bring up their children. Some researchers argue that microbes passed from mother to child could also help explain associations between parental environments and offspring outcomes. All of these factors are difficult to rule out in studies of epigenetic inheritance.

INHERITANCE OF ACQUIRED TRAITS: FROM LAMARCK TO NOW

Although theories of epigenetic inheritance have drawn new interest in the last 20 years or so, the ideas they tap into have been around for centuries.

| Jean-Baptiste Lamarck hypothesizes that traits an animal acquires during its lifetime—an extended neck after years of stretching up to reach high leaves, for example—can be inherited by future generations. He proposes that this idea, versions of which have been circulating since ancient Greek times, explains how species evolve. |

| Soviet agriculturalist Trofim Lysenko rejects decades of genetics research while pushing his own theory of how traits that organisms acquire in their environments can be inherited. He’ll use the idea to develop disastrous agricultural policies that contribute to crop failure and famine. |

| Embryologist Conrad Waddington coins the term “epigenetics” to describe the developmental processes that connect an organism’s genotype to its phenotype. The term will later be coopted to describe work in other disciplines, including research on the regulation of gene expression. |

| Research on chromatin structure takes off, with DNA methylation and histone modifications becoming associated with variation in the expression of particular DNA sequences. It will be many years before the research becomes known as epigenetics. |

| The discovery of imprinted genes—sequences that are methylated at an organism’s birth and whose expression depends on which parent they were inherited from—launches the idea that DNA methylation carries information from parent to child. |

| The number of papers including the term epigenetics soars, and the idea that the field offers an alternative to genetic explanations for inheritance gains traction in the public eye. News stories claim that the field is “rewriting the rules” of heredity. |

Read the full story.