ABOVE: © ISTOCK.COM, NeoLeo

Scientists know a lot about apoptosis, from its molecular control to pathways that stop the cell death process in its tracks, but being able to control when and where it occurs would help researchers glean more details about its role in development. To that end, chemical biologist Steven Verhelst of KU Leuven in Belgium and his PhD student Suravi Chakrabarty decided to use a technique called photocaging to make an inhibitor of caspases, enzymes involved in apoptosis, that can be controlled by light.

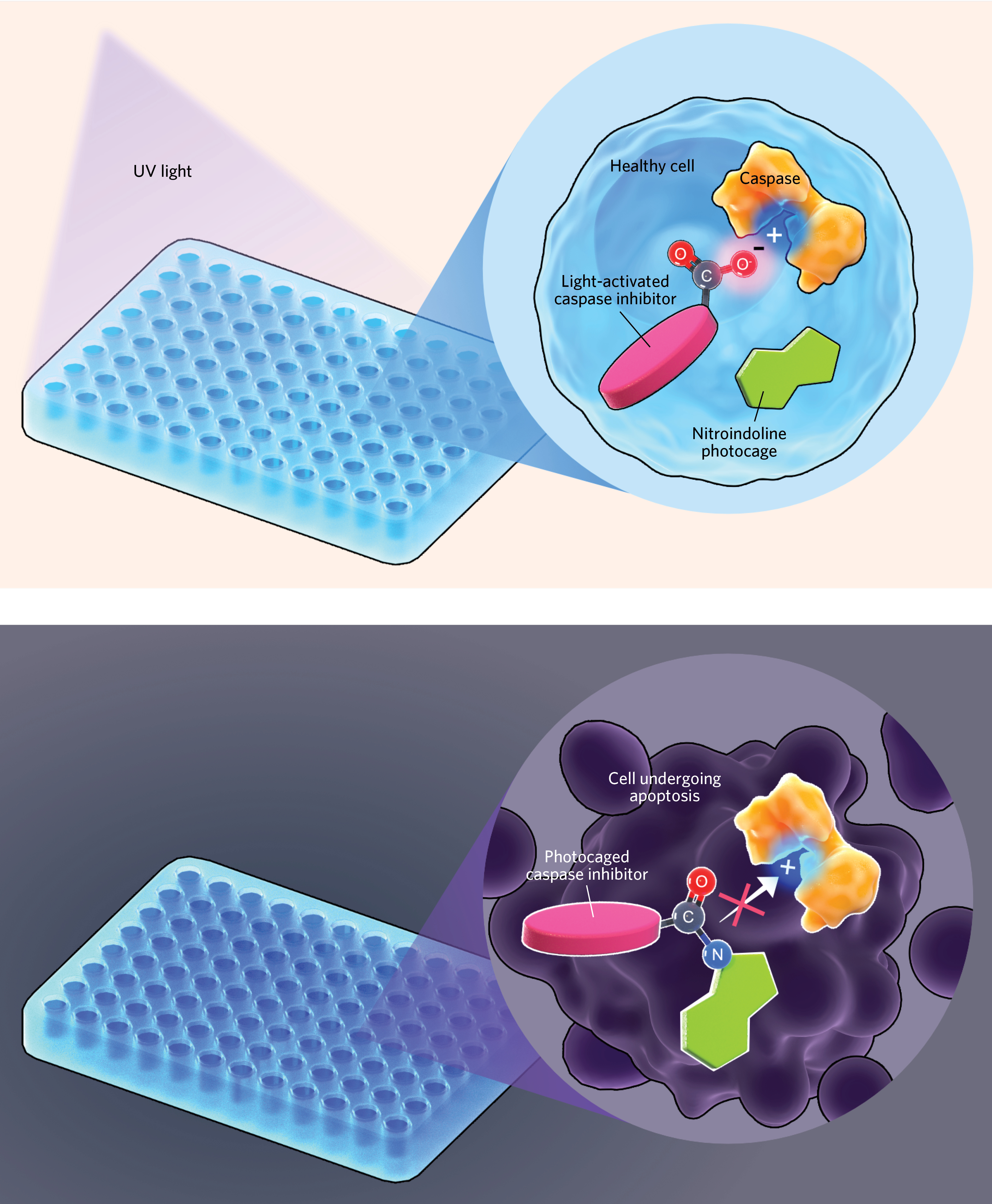

For a small molecule to effectively inhibit a caspase, it needs a negative charge in just the right spot to fit into a positively charged pocket of the enzyme. Verhelst and Chakrabarty decided to develop a molecule that had a photocage, a chemical group that sat on top of that negative charge and prevented the inhibitor from binding and stopping the caspases from carrying out apoptosis. “If we could block that negative charge, we would virtually know—well, say, 99 percent sure—that it wouldn’t inhibit the protease,” Verhelst says. Light could then be used to release the inhibitor from the photocage at a specific time and location, he and Chakrabarty reasoned.

They synthesized caspase inhibitors with various protecting groups to serve as photocages, and found one, using nitroindoline, that was stable in solution for at least three days. The duo then irradiated the nitroindoline-photocaged inhibitor with UV light to test whether it would cleave the carbon-nitrogen bond linking the photocage to the inhibitor. “It took only five minutes for all the protease in the sample to become active,” Verhelst says. Then, he and Chakrabarty tested their photocaged inhibitor on purified caspases, cell lysates, and finally, cells in culture.

The researchers incubated human T cells with reagents to induce apoptosis, the new inhibitor, and a molecular marker that fluoresces green in apoptotic cells, and imaged the cultures every two hours. In samples that were not exposed to UV light, the caged inhibitor did not stop caspases from carrying out apoptosis and all the cells died, but in samples exposed to 15 minutes of UV irradiation, apoptosis was fully inhibited. “Our caged inhibitor, [once] irradiated, . . . gave almost the exact same result as the non-caged inhibitor,” Verhelst says.

“I have to give them credit for the amount of work they put into this thing,” Thomas L. Brown, a cell and molecular biologist at Wright State University who has studied caspase inhibitors and apoptosis and whose company, Apoptrol LLC, markets a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor. It’s a challenge to modify caspase inhibitors, he says, “because usually you kill them—you just stop them from working.” The authors “did a good job figuring it out. . . . The data’s really solid,” Brown says, but he adds that the photocaged inhibitor is limited in its application, in part because UV light does not penetrate deep into tissue.

Verhelst says his team would like to develop inhibitors that can be activated by infrared or near-infrared light, which can reach several millimeters into skin, to overcome some of these limitations, but for now he plans to use the photoactivated caspase inhibitor in transparent zebrafish embryos. Apoptosis is essential in the development of multicellular organisms, and inhibiting this form of cell death at various stages of embryonic growth could shed light on “the function of apoptosis at very specific places and times,” Verhelst says, adding that he also hopes to develop light-controlled inhibitors of other proteases.

“It’s kind of a foundational study that you can, one, cage [the inhibitor], and two, uncage it, with—at least right now—UV light,” Brown says. “But that opens the door for unraveling other mechanisms of activation that do not include UV for use in more complex systems.”

S. Chakrabarty, S.H.L. Verhelst, “Controlled inhibition of apoptosis by photoactivatable caspase inhibitors,” Cell Chem Biol, doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.08.001, 2020