ABOVE: A fecal microbiota transplant capsule filled by staff at OpenBiome

COURTESY OF OPENBIOME

Update (December 1, 2022): The US Food and Drug Administration announced yesterday that it has approved its first fecal microbiota product, Ferring Pharmaceuticals’ Rebyota, for prevention of recurrent C. difficile infection in adults.

Alexander Khoruts wishes we’d all stop using the F-word. In addition to its yucky connotations, the term “fecal transplant” is an inaccurate description of the procedure he helped pioneer, he argues, since “you can’t transplant feces.” Rather, it’s the intestinal microbiome that gets engrafted, says Khoruts, a gastroenterologist at the University of Minnesota who coauthored the first detailed how-to guide for the procedure. Accordingly, he says, he prefers the term “intestinal microbiota transplant.” As director of the university’s Microbiota Therapeutics Program, he regularly works with people who undergo the procedure, and “I’ve seen the patients really have a sigh of relief when you lose the ‘fecal’ word.”

Khoruts realizes that the term fecal microbiota transplant, or FMT, is likely here to stay, however. The procedure, which involves transferring carefully screened donor stool via colonoscopy, enema, or a pill, has gone mainstream over the past decade. FMT is now a go-to treatment for recurrent or refractory infections with a bacterium known as Clostridium difficile (C. diff for short), which causes sometimes debilitating gastrointestinal symptoms and can be fatal if not successfully treated. Researchers are also investigating the efficacy of FMT for a range of other conditions.

Khoruts and other observers say the use of FMT is poised for major changes with the expected entry onto the market of commercial microbiota therapeutics that consist of processed stool components or consortia of lab-grown intestinal bacteria. While many clinicians who perform FMT expect these changes to be largely positive, some, including Khoruts, have concerns about how they might affect patients’ access to treatments.

FMT gains in popularity

The use of FMT to treat C. diff dates back decades; one of the first case studies on its successful application was published in 1983. But the procedure didn’t spark widespread attention until the turn of the millennium, when, faced with the rise of increasingly virulent and antibiotic-resistant strains of the bacterium, doctors starting searching for new ways of helping patients who didn’t respond to antibiotics, or whose infections would subside only to recur again and again. In some cases, antibiotics even seemed to promote C. diff infection, with the bacteria taking hold after the commensal microbiota had been depleted by the drugs. Patients often acquired C. diff while in the hospital being treated for other conditions.

I would love to just have a product that I can prescribe, and that’s passed through all the regulatory hurdles and has FDA approval and is covered by insurance.

—Krishna Rao, University of Michigan

In the early 2010s, evidence for FMT’s efficacy against recurrent C. diff infection accumulated, and many academic medical centers began to offer the procedure. Patients would often be asked to recruit their own donor, such as a family member, and if that person tested negative for infectious diseases, their fresh stool would be homogenized with saline solution or milk in a household blender, filtered, and then administered. But there were hurdles to offering FMT. At the University of Michigan (UM) medical center, which started performing the procedure around 2012, gastroenterologist and researcher John Kao recalls that it was difficult to get permission from hospital administrators. “I have comments like, ‘What are you doing? This is like bloodletting.’” Additionally, because FMT is not a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved treatment, UM had to file an investigational new drug (IND) application to offer it.

The rise in FMT’s availability really began in 2013, when the FDA announced that it would exercise “enforcement discretion” by no longer requiring INDs for the use of FMT in recurrent or refractory C. diff infections. OpenBiome, a nonprofit stool bank that had started up in 2012 with the aim of supplying local hospitals treating C. diff patients, saw that 2013 decision as an opportunity to expand, says Carolyn Edelstein, the organization’s executive director. “When the FDA issued enforcement discretion, we saw increasing need from the clinical community that was offering FMT, wanting to be able to just make sure that they could directly treat patients,” she says. “And so we began scaling up to meet the interest in using FMT to treat C. diff patients who weren’t responding to standard antibiotic therapies.” Over time, OpenBiome came to supply most clinics in the US that offered FMT—including many that, like UM, had started out by screening donors and preparing stool themselves.

Screening of FMT products becomes more rigorous

An advantage of obtaining FMT material from OpenBiome is that the organization handles the necessary pre-transplant screenings. “As time has gone on, the screening has gotten more and more involved and more in depth,” both for donors and for the stool, explains Stacy A. Kahn, a professor at Harvard Medical School and director of Boston Children’s Hospital’s FMT and Therapeutics Program. “There’s no cost-effective way for an individual provider to adequately screen the stool as comprehensively” as a stool bank such as OpenBiome, Kahn says.

The importance of this screening has been highlighted in recent years by high-profile safety incidents linked to FMT, including a patient death at Massachusetts General Hospital in 2019 that was ascribed to antibiotic-resistant E. coli in the donor’s stool, and six infections with pathogenic E. coli after FMT with stool from OpenBiome that prompted an FDA warning last year. The FDA noted in its warning that FMT with contaminated stool might also have contributed to the deaths of two other patients, although this could not be definitively determined. OpenBiome announced changes to its screening protocols at the time of the warning, while also arguing that the deaths were unlikely to be due to FMT.

From July 2020 until this May, OpenBiome stopped providing FMT materials except in emergency cases as it worked to develop and validate a test for SARS-CoV-2 in stool. For emergency cases, it used stock collected before December 1, 2019. The organization announced this February that, due to financial difficulties and the likely entry onto the market of FDA-approved commercial microbiota therapeutics for C. diff, it will be phasing out its services. OpenBiome isn’t planning on going away, says Edelstein, but will instead focus on supporting microbiome researchers—for example, with its library of more than 100,000 human stool aliquots.

Companies work on drugs destined for FDA approval

Even before high-profile safety issues cropped up, some companies spied an opportunity to develop an easier-to-use and more consistent FMT product. Around a decade ago, FMT was “forcing doctors to be manufacturers and manufacture a drug,” says Ken Blount, chief scientific officer of microbiota therapy company Rebiotix, which started up in Minnesota in 2011. “And that ultimately means the FMT you get . . . in Connecticut versus San Diego versus Boston is a different thing.” The lack of an FDA-approved product also means that FMT isn’t available everywhere, he adds, and usually isn’t covered by insurance.

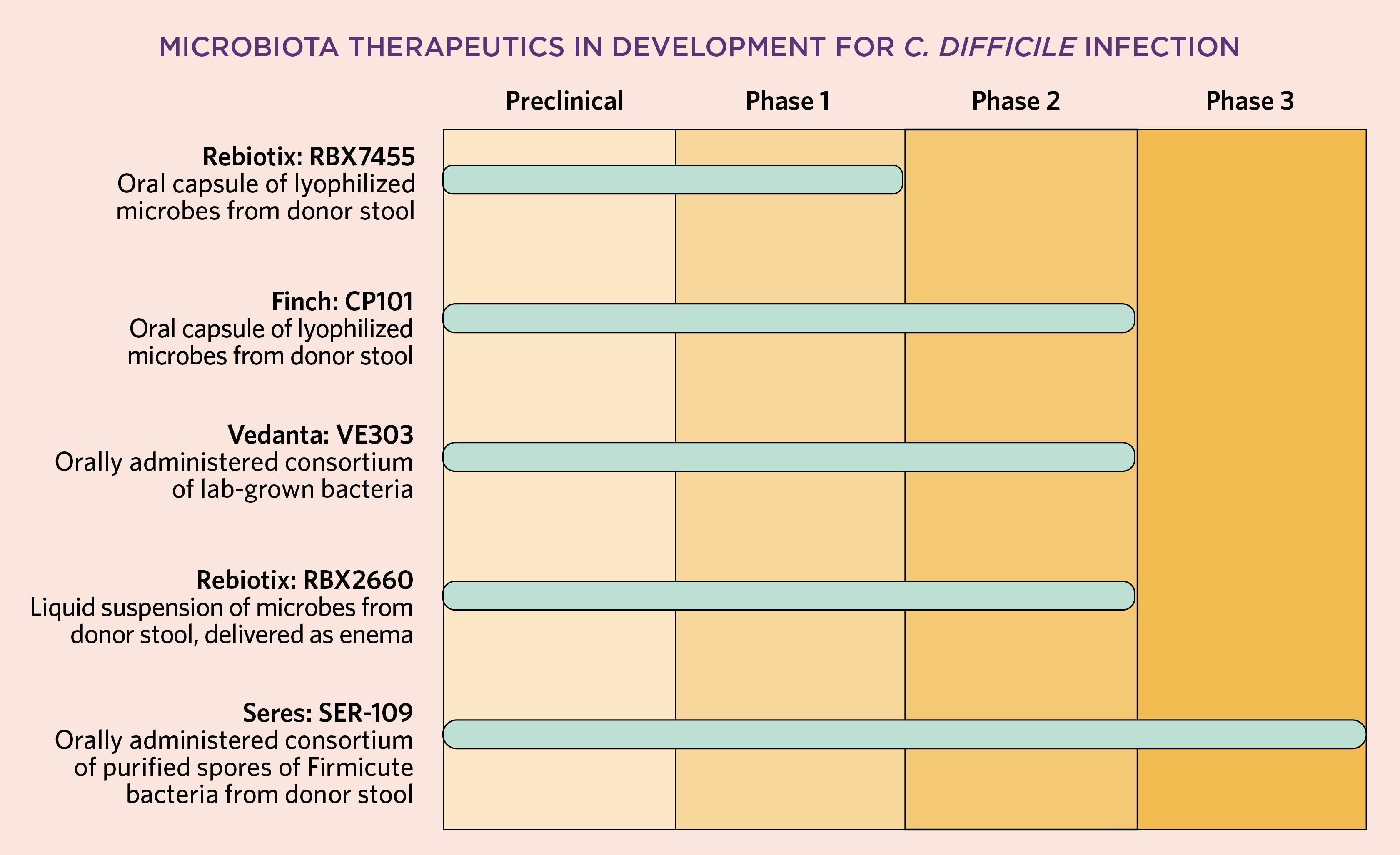

To plug this gap, Rebiotix began developing what it calls a Microbiota Restoration Therapy with the goal of obtaining FDA approval. Rebiotix’s product, dubbed RBX2660, now in Phase 3 testing for recurrent C. diff infection, is not only screened for safety but also tested to ensure that it contains a certain amount of viable bacteria per dose, Blount says. [Update: After the print version of this article went to press, Rebiotix reported positive Phase 3 results.] RBX2660 is designed to be delivered via enema; Rebiotix also has a second, oral formulation in development.

Another product nearing the end of the development pipeline is Seres Therapeutics’s SER-109, for which the Massachusetts-based company announced positive Phase 3 results last year. That orally administered product consists of a consortium of bacteria purified from stool in which all live organisms have been killed, leaving spores behind. Finch Therapeutics, also headquartered in Massachusetts, has a stool-based product that has completed Phase 2 testing; a spin-off from OpenBiome, Finch is headed by Edelstein’s husband, Mark Smith, who previously served as OpenBiome’s president and research director. Nearby Vedanta Biosciences has developed a non-stool-based consortium of bacteria that has also undergone Phase 2 testing for recurrent C. diff infections.

Khoruts predicts that once a commercial microbiota therapy is approved for recurrent C. diff infection, clinics will move away from providing traditional FMT with either their own preparations or OpenBiome’s material. That’s due to the costly screening process needed today, he says, and to concerns about litigation risk should safety issues crop up with a homemade product that isn’t FDA-approved.

Other clinicians who spoke with The Scientist largely concurred with that prediction, while noting it will depend somewhat on as-yet-unknown factors such as how much companies charge for the therapies and whether insurance companies cover them. “I would love to just have a product that I can prescribe, and that’s passed through all the regulatory hurdles and has FDA approval and is covered by insurance,” says Krishna Rao, the medical director of the fecal microbiota transplant program for C. diff infection at the University of Michigan and a consultant for Seres. Reezwana Chowdhury, a gastroenterologist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, likewise says she’s “excited about all the things that will be coming out into the market. And I do think it’s going to give our patients more options.”

Experts raise concerns about accessibility

Despite this overall optimism, there is a possibility that replacing the current sourcing system with commercial products could inhibit access to these treatments, some experts note. Khoruts, who helped develop a process for making an oral formulation with freeze-dried bacteria that was licensed by Finch, says he’s concerned companies could charge prohibitively high prices for their microbiota therapies, leading insurance companies to “put up barriers of some kind” that make it difficult for patients to get the therapeutics. Khoruts’s program manufactures its own capsule-based microbiota therapeutic for recurrent C. diff, which he says patients aren’t charged for. He says he’d like to scale that up by starting a nonprofit that could supply clinicians throughout the country whose patients couldn’t otherwise access FMT—but there are legal barriers to doing so, again because of litigation risk.

Pediatric patients are a group that’s particularly at risk of losing access to FMT with OpenBiome’s planned phaseout, says Kahn. C. diff infection isn’t as common in kids as in adults, she says, but as with adults, its prevalence has been increasing in recent decades. “I think that people don’t understand how debilitating this is for kids,” who commonly spend so much time in the bathroom that it’s difficult for them to attend school or participate in activities, Kahn elaborates. Companies aren’t currently testing their microbiota therapeutics in children, and while commercial therapies could potentially be used off-label in pediatric patients, Kahn says, insurance is unlikely to cover that.

While the move to commercial products could create access issues for some patients who would benefit from FMT, it could also make the therapy available to patients who are unlikely to benefit. FDA’s enforcement discretion notice was specific to the use of FMT for C. diff infection that doesn’t respond to other therapies, meaning that treating other conditions with stool still requires an IND. But preliminary experimental results suggesting FMT could also be an effective therapy for ailments ranging from intestinal disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease to cancer to autism have raised excitement among patients and their families that outstrips what’s currently clinically feasible, providers say. “We sometimes have patients cold calling asking for FMT for a variety of indications beyond C. diff,” says Lea Ann Chen, a gastroenterologist at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson School of Medicine in New Jersey.

In reality, treating other indications with FMT likely won’t be as straightforward as it has been for C. diff, Chen says. “For whatever reason, with C. diff you don’t have to be that selective about the donor stool—clearly there are safety things and screening that we do for infectious agents, but beyond that it seems like most acceptable donor stool will work for any patient,” she says. For other conditions, studies so far indicate that “there seems to be some matching that needs to happen in order to have that effect, and we still don’t fully understand why certain patients do well and why certain donors seem to be better than others.”

Given these circumstances, Khoruts says he’s worried about the potential for FMT to be prescribed inappropriately, because “once something is approved [for one condition], physicians are free to use it for other things off label.” Unless the FDA steps in to restrict off-label uses, “there’s going to be potential for abuse of misappropriating these drugs for something that we don’t know how to use them for,” he adds. Sahil Khanna, who leads the Mayo Clinic’s FMT program for C. diff, agrees: “We need to set up some guardrails to avoid off-label use, to prevent potential harm to people.”

The future of microbiota therapeutics

There are some microbiota therapeutics already in the pipeline for disorders other than C. diff infection, although they are not as advanced. Vedanta, for example, has therapeutics in development for inflammatory bowel disease, solid tumors, food allergy, and multidrug resistant organisms, while Rebiotix is developing products for vancomycin-resistant enterococci infection, pediatric ulcerative colitis, drug-resistant urinary tract infections, and a condition involving the buildup of ammonia in the liver.

In the long run, Edelstein says, she expects that the field will move further from its fecal roots once researchers pinpoint the types of bacteria that can effectively treat various disorders. “Once we have reliable access to products that are directly sourced from humans, we think the next step is to help make sure that we can isolate and identify those strains that can potentially be a key component of future therapies.”

Correction (June 3): A previous version of this article stated that the use of FMT to treat C. diff dates back nearly 40 years. In fact, FMT may have been used for C. difficile infection in 1958. The Scientist regrets the error.